Two weeks ago, my son had his first serious opportunity to play the guitar. After years of standing in front of me and beating on my strings, he has had his turn to embrace an instrument of his own and find his way through the deep roads of the fretboard, the strings, bridge and pick. There is much ahead in his journey to even determine if he wants to play the guitar but for now he has one of his own to lean over or hug as it rests on his right thigh.

Chords remain a work in progress. The fingers and the spatial arrangement have not visited each other frequently enough for him to feel adept at putting together a chord and his hands still have a bit of growing to do before we get into a discussion of bar chords or the challenge of reaching the furthest strings. For the time being he has beaten on his guitar along with everyone else, a contribution of vibe or passion to the more structured strumming and chord progressions the rest of us follow. While we were proceeding through Pink Floyd's "Wish You Were Here" his head was tilted back, his eyes were closed and his pick-hand was well over his head - a tribute to Pete Townshend before he even discovered the man's technique of idiosyncrasies. He seemed to be in complete rapture and lost in the moment. As I beamed at him, his eyes opened and he dissolved into a state of self-consciousness.

"What?", he asked, his rapture dissolved and chased by a newly discovered timidity.

I assured him that all was well and did my best to assure him that -- as far as I was concerned -- that moment of lost bliss was just what the guitar was about. Since that moment, however, I have wondered about what it would take to introduce him to the concept of the zone or peak performance. I recall my own efforts to get into the zone when I was learning to ride the bicycle. My first was a gleaming green with a long banana seat and high handlebars like you'd associate with a chopper. There were no training wheels in the effort. This was strictly old school and the effort to find my balance was a lengthy one. History would probably say that the learning was briefer than I recall but I rode up and down a stretch of yard that ran next to the house, wobbling along until I completely fell over until, bang, I had it. For some reason I fell upon the word "Cordoba" (after the Chrysler) and ran that word through my head repeatedly until gravity pulled me off the bike and dislodged my mantra. I would resume again and again, the word stuck in my head until I was balanced and able to bring myself to a controlled stop rather than a fall. I do not recall if I did a full lap of the yard or if I just felt that I, after going all of 10 metres without falling over, just assumed I had the bike thing all sorted out. It was, however, a stretch where I was in the zone as I tried to master the bike.

The guitar was much later for me and while self-taught, there was a bit more self-critique and a lot more inner dialogue than I would have had if I started as early as my son. At this point, he is not too concerned about precision or proficiency - he just wants to bang on the guitar and enjoy the social aspects of sitting amongst "the men" to indulge in the time they share.

I want to find a way to make him familiar with that peak experience. Regular experience of it will provide him with the compass to his passions and his purpose. It will also clarify his definition of himself and the things he does well or may be meant to do. It does not have to come from playing the guitar or music. I just want him to be familiar with it and have the conversation with him about what it is, how he got there and what it might mean. I suspect that it will wait, but in the meantime, I'll file moments like this one to tell him about these experiences and ask him to reflect on how he felt during those moments.

Showing posts with label creativity. Show all posts

Showing posts with label creativity. Show all posts

Monday, June 5, 2017

Friday, June 17, 2016

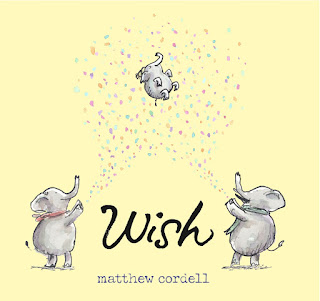

Books For the Inner Child

With some kids lit or entertainment there is the unique pleasure of the wry wink to the adults. Something about rabbits being good at multiplication in Zootopia, a sight gag that pays homage to the Godfather trilogy or a wry, sly pun that lets the reader know that the author knows who actually has to read the book. Perhaps one of those elements lies dormant in a child's memory or imagination like a buried treasure awaiting maturity for revelation.

With some kids lit or entertainment there is the unique pleasure of the wry wink to the adults. Something about rabbits being good at multiplication in Zootopia, a sight gag that pays homage to the Godfather trilogy or a wry, sly pun that lets the reader know that the author knows who actually has to read the book. Perhaps one of those elements lies dormant in a child's memory or imagination like a buried treasure awaiting maturity for revelation. I have, however, come across children's books that leave me wondering if a child needs the message or moral of a story. Maybe it is a little early for a child to think seriously about the place you will actually go as Dr. Seuss described them and as my Philosophy of Education professor read to the class at the end of our year with him. He was, with Oh, The Places You Will Go, an early adopter, one who had identified adults' needs for that particular message and shared that with my classmates and I in 1990 without any trace of irony or the weariness that might have followed 10 or 15 years later when it was, like many aptly-written stories or lines, unfairly rendered cliche.

I have, however, come across children's books that leave me wondering if a child needs the message or moral of a story. Maybe it is a little early for a child to think seriously about the place you will actually go as Dr. Seuss described them and as my Philosophy of Education professor read to the class at the end of our year with him. He was, with Oh, The Places You Will Go, an early adopter, one who had identified adults' needs for that particular message and shared that with my classmates and I in 1990 without any trace of irony or the weariness that might have followed 10 or 15 years later when it was, like many aptly-written stories or lines, unfairly rendered cliche. With the exception of the countless variations on stories of fire trucks at work and similar tales, there are stories with clear messages in them that are both a pleasure to pass down as they are to share. Whether it is the criticism of tyranny in Seuss' Yertle the Turtle (to name only one of his) to the more recent description of the boundless and growing unconditional love Nick Bland describes in The Runaway Hug or the timelessness of friendship in Marianne Dubuc's buried treasure of The Lion and the Bird, those theme-rich children's stories thrill me when they come down from the shelf.

With the exception of the countless variations on stories of fire trucks at work and similar tales, there are stories with clear messages in them that are both a pleasure to pass down as they are to share. Whether it is the criticism of tyranny in Seuss' Yertle the Turtle (to name only one of his) to the more recent description of the boundless and growing unconditional love Nick Bland describes in The Runaway Hug or the timelessness of friendship in Marianne Dubuc's buried treasure of The Lion and the Bird, those theme-rich children's stories thrill me when they come down from the shelf.

There are other stories that make me wonder if a child actually needs to hear them. Or, to be more specific, whether my four-year-old needs to hear them yet. The first story that comes to mind is The Little Prince, which -- length aside -- might simply prompt a child to say, "Well, of course" at each of the passages from the book the adults hold onto like talismans or mantras to navigates them through the baffling rationalizations and foibles adults find themselves prone to.

Beyond that classic, there are other stories that I have come across that baldly express to adults something that we need to hear. Koji Yamada's What Do You Do With An Idea is the compact and beautiful complement to the numerous weighty tomes on creativity that have emerged like April dandelions in the last few years. It foregoes the theory, the psychological research, priming exercises and reflective practices that so many adult-oriented creativity books contain in favour of an extended poem about the life span of an idea. Yamada points out all the stages along the way from the nascent discovery of a thought to changing the world in a matter that one can memorize over time. This is not to say that a child would not get it - just that they are more likely to think, "Well, of course."

Beyond that classic, there are other stories that I have come across that baldly express to adults something that we need to hear. Koji Yamada's What Do You Do With An Idea is the compact and beautiful complement to the numerous weighty tomes on creativity that have emerged like April dandelions in the last few years. It foregoes the theory, the psychological research, priming exercises and reflective practices that so many adult-oriented creativity books contain in favour of an extended poem about the life span of an idea. Yamada points out all the stages along the way from the nascent discovery of a thought to changing the world in a matter that one can memorize over time. This is not to say that a child would not get it - just that they are more likely to think, "Well, of course." In his book The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettelheim talks about the distinction between the conscious, subconscious and the preconscious, saying that it is intrusive to make our preconscious thoughts conscious. Stories can help us ensure those preconscious aspects of our character or our interpretation of the world are reinforced and perhaps ensure a child that it is okay to believe certain things that might be drawn into doubt at times that would make even a four-year-old ask, (as he has), "What is this world coming to?!"

In his book The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettelheim talks about the distinction between the conscious, subconscious and the preconscious, saying that it is intrusive to make our preconscious thoughts conscious. Stories can help us ensure those preconscious aspects of our character or our interpretation of the world are reinforced and perhaps ensure a child that it is okay to believe certain things that might be drawn into doubt at times that would make even a four-year-old ask, (as he has), "What is this world coming to?!"For adults, getting lost and reassured in a lesson on creativity, the whimsy of a desert-stranded pilot's reflections or hallucinations on adulthood and mortality or a mantra that assures you of what makes a family a family seem better suited for adults in need of the courage or evidence to believe in certain possibilities at a time where the safest place in the world is in a bedtime fortress of pillows and blankets burrowing into an illustrated truth delivered from a wise, succinct storyteller.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)